My Experience Teaching English in Nepal (Part III)

About This Resource

Details

Part III: Who is Teaching Whom?

By Denitsa Gancheva

[This is part III in a series of blog posts about my personal experience teaching English at the Maratika Monastery in Nepal. Here you can find Part I and Part II.]

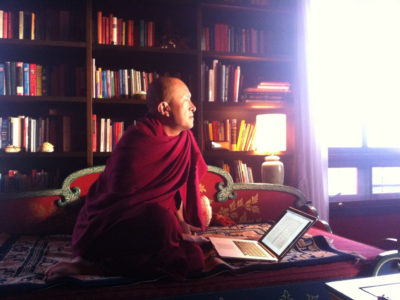

Interacting with the students at Maratika often prompted me to reflect on a typical teacher–student relationship. The way even I had experienced education as a child was as a relatively one-way interaction with limited input from the students in the educational process. The way English lessons work in a monastic environment, however, seems to rather call for a lot of flexibility, improvisation and openness to changes in the monks’ daily routines and interests.

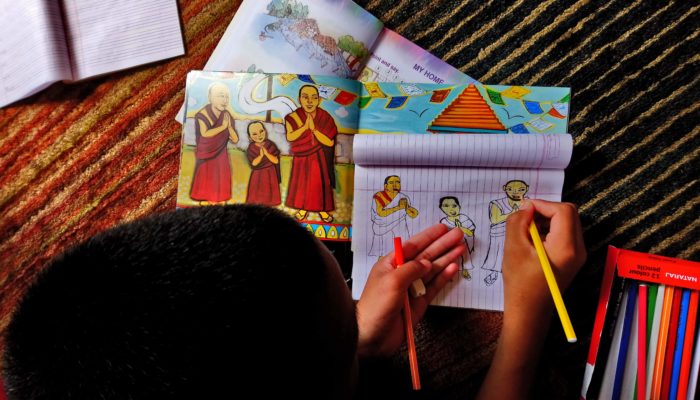

About a month after my lessons at Maratika Monastery had started, the monks and I were going through a picture book with different topics in English—numbers, colors, fruits and vegetables. In the book, there was a double-page dedicated to the singular and plural nouns. One of the pictures was of a louse and its plural—lice. The monks recognized and started pointing to the image (body lice could sometimes appear, especially during the warmer months), so I had to explain: “this is one louse, and these are many lice.” For some reason the youngest monks were delighted and after class they were running around the yard, laughing and in pure joy singing “One louse, many lice; one louse, many liiiiiiice.”

This little episode made a big impression on me – the monks’ pure acceptance of lice as a non-dual object, neither good, nor bad, as opposed to the shame that we, in some parts of the world, feel towards even admitting their existence. I believe that the precision with which Buddhist philosophy was taught, and the level at which it was ingrained in daily life, allowed this community to be genuinely curious and generally non-judgmental about their environments.

At the monastery things just were. What if I could also just be during class – no rigid expectations and planning but an open mind to whatever presents itself?

I had been studying Buddhism and this seemed like an ideal opportunity to practice some of its teachings.

The way we traditionally experience education in most of Europe and North America is quite straightforward: the teacher prepares a programme, which is then followed in class and students are evaluated based on it. There is often a sort of teacher-student divide, and a limit to the input from students in the educational process.

I wanted to see what would happen if I took an inquisitive, investigative approach to my teaching and class structure. My plan was simple – I still intended to go to class prepared, I gave homework and tests, and was insistent about paying attention during a lesson. At the same time, I wanted to balance this with giving ownership to the students and being tuned in with their state of mind. Sometimes it was impossible to have them focus on what I had planned. So why force on them material that won’t keep their attention and likely won’t stay in their memory? During these days we would read a book, play educational games, draw and write, or explore the map of the world and talk about the different countries.

Letting go of my plan and co-creating the lesson with my students was liberating and, I believe, had positive results in their motivation and discipline. A teacher–student symbiosis, rather than hierarchy.

Slowly I also became less anxious about sitting in silence with them, especially at the beginning of a class. Silence brings a quality to any communication and is a useful check-in tool. A teacher is almost expected to fill all gaps with knowledge, but in a Buddhist setting, it is easier to remember the importance of slowing the mind down and allowing for spaciousness and deep breath.

There was also another precious advantage to teaching English to monks – they are generally used to repetition and able to focus for good chunks of time. There is no need to constantly draw their attention back in or do a different exercise every 15 minutes; they are able to repeat the same material until the teacher has decided that they have understood it.

While their ability to memorize is exceptional, they need a lot of support when it comes to open-ended conversations, expressing preferences and applying an existing knowledge to new areas. “What is your favorite color? -Red!”; “What do you like to do in your free time? -Play football!” If one monk would give me these answers, without a doubt those same answers would echo throughout most of the classroom.

During my months at Maratika, I had many such observations and thoughts, constantly informing and shaping my approach to teaching. I believe my students taught me more than I had the chance to teach them. I am still reflecting and trying to place all this insight into one coherent picture. It definitely seems to me that an open, balanced and mindful education is what our societies need nowadays. In my opinion, that should combine the wisdom, compassion and non-duality of Buddhism with modern/Western educational techniques of developing critical and creative thinking. Luckily, places like the Middle Way School and Abiding Heart Education are already working in that direction. Even organizations like UNESCO have started discussing how we can rethink education in view of social and emotional learning, for example here.

As for me, personally, during the months at Maratika, the monks rekindled a sort of pure wonder towards the world. I learned a lot about joy, respect, staying curious and enjoying the flow of life. I believe these are all essential qualities for any teacher.