How to Create a Dharma Culture at Home

About This Resource

Details

LINK TO COMPLETE ARTICLE

How to Create a Dharma Culture at Home

by Sumi Loundon Kim

When adults teach meditation and Buddhism to children, we tend to reach for direct instruction, exercises, and activities. Certainly, this modality has a significant impact: when I was seven, my father began instructing me on abdominal breathing, pranayama, and breathing meditation. These lessons have stayed with me ever since. But equally impactful are indirect ways of teaching that allow for passive absorption.

Let me suggest three low-effort modalities you can implement at home, drawn from my childhood experience of Buddhism, my learning curve as a mother of two (now 12 and 14), and my work as program director and teacher with the Mindful Families of Durham in North Carolina.

Sacred Space

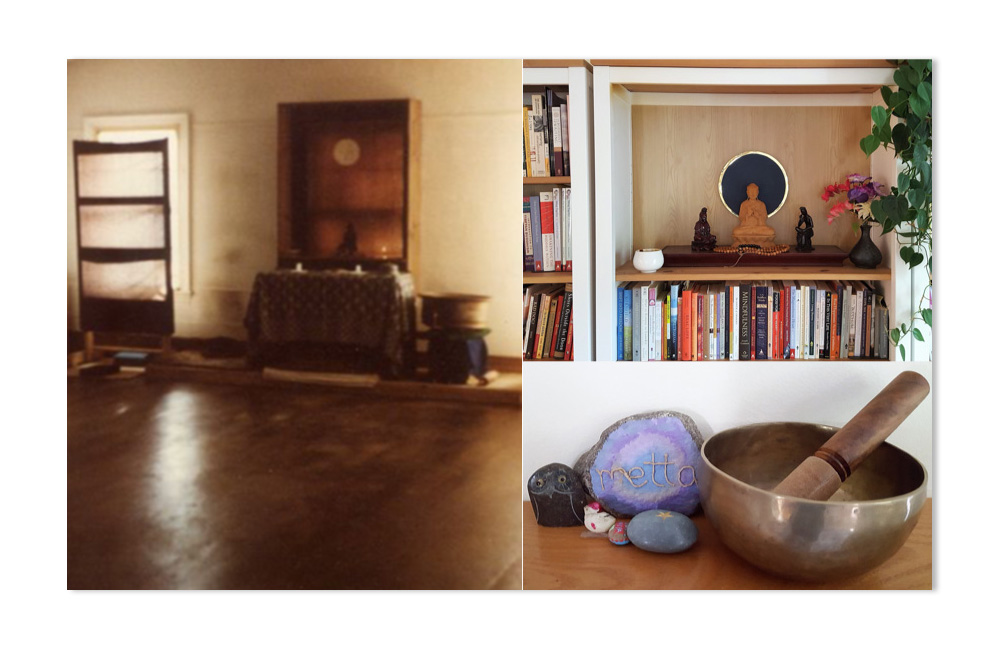

Zendo from my childhood, with Buddha statue and “truck hub” gong. My meditation spot is on the very far left in the photo. Circe late 1970s.

I grew up in a Zen center in rural New Hampshire until I was just shy of nine. In the main meditation hall…