The Gore and the Good of the Jataka Tales

About This Resource

Details

In this article I explain how my negative view of the Jataka Tales changed.

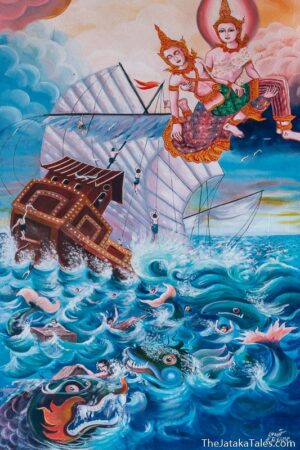

The Jataka Tales are an ancient collection of stories originating from the Indian subcontinent that were passed down through the ages, first as an oral tradition and later transcribed and translated into many languages. They are essentially the past life stories of the Buddha: stories of when he was a tiger or a beggar, an elephant or a king, but always a bodhisattva. There are about 550 of them, although some of those 550 only have titles and some have no titles.

Most published versions are full of violence, aggression, misogynistic stereotypes, and other tropes that I felt were not relevant to today’s learners. For example, there are stories about owls who eat crows’ heads, greedy mothers, a son cleaving his father’s head open with an axe in order to kill a mosquito, spirits devouring men and scattering the bones, people so angry their hearts explode out of their mouths, vain women being reborn as dung worms, and so on. Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche once told me that we should be cautious about the media we consume, watching violence, gore, and bad behavior can create a karmic imprint. We might become accustomed to these images and recreate them in our next lives. At the very least they might penetrate a child’s dreams and give all involved a bad night’s sleep.

Related Resources

Morning Movement with the Harmonious Friends

Selected Jataka Tales

The Clever Fox: A Guided Meditation for Children

The Jataka Tales of Dunhuang Worksheet

About The Contributor

Noa Jones is the founder and executive director of Middle Way Education and was the founding Chair of the Middle Way School of the Hudson Valley, which she was asked to create as a laboratory to develop a new model of Buddhist education for modern learning environment. She taught at MWS for 6 years and received a masters degree from the graduate school of education at the University of Pennsylvania. She is also a writer of fiction and creative nonfiction. Previously, she worked for Khyentse Foundation for 17 years.